All Spin Bayesian Neural Networks

Published:

A simplified explanation of the project I worked on during my undergraduate thesis in the Neuromorphic Computing Lab under the supervision of Dr. Abhronil Sengupta. The work was a collaborative effort among all the lab members at the time.

Briefly explain the problem you worked on.

The problem I worked on is the hardware acceleration of Bayesian neural networks using spintronic devices. Hardware acceleration is the design of special-purpose hardware so that certain functions can run more efficiently (lower power consumption, faster execution, etc) than they would run on a general-purpose CPU. A common example of hardware acceleration is the graphical processing unit (GPU), which performs various complex mathematical and geometrical operations for graphics rendering more efficiently than a general-purpose CPU.

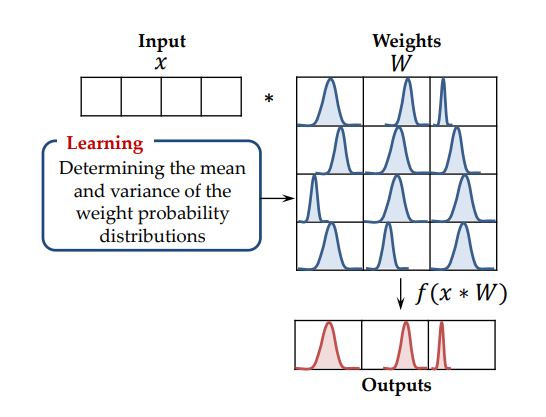

Bayesian neural networks (BNN) are structurally similar to traditional neural networks. The fundamental difference between the two is that the weights of a BNN are probability distributions rather than fixed-point values. These distributions are generally modeled as Gaussian distributions, each having its own mean and variance. During the training stage, the best set of means and variances are obtained for each weight, so that the network can make predictions with maximum accuracy. Figure 1 shows the forward propagation of input data through the network. When data is inputted into the network for prediction, the weights used are sampled from their respective probability distributions. Therefore, if this process is repeated multiple times, the final output of the network can be characterized as a probability distribution, with a certain mean and variance, rather than just a fixed point value.

Figure 1: Forward propagation of data through a BNN

Spintronic devices are an emerging technology that utilizes both the electric charge and the spin of the electron for logic and memory applications. The basic device structure used in this work is the Magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ), which is a two-terminal device consisting of two nanomagnets sandwiching a metal oxide layer. I’m not going to go into the details of the device structure, but here are some fundamental things to know. Firstly, the resistance of the device depends on the relative spin of the electrons of the two nanomagnets: if the spins are in the same (opposite) direction, the device is said to be in the parallel (antiparallel) state and possesses its lowest (highest) possible resistance. Secondly, since the state of the device is stored in its spin, it is able to retain its state without any external power supply (unlike an SRAM cell, which stores the bit only when power is on). Thirdly, the device can be used either as a two state (parallel and antiparallel) device with just two possible resistance values or a multi-state (many states between parallel and antiparallel) device with multiple possible resistance values. I’ll talk more about how to switch between the states of an MTJ later.

One thing to keep in mind is that the hardware I designed was for a BNN which has been trained offline. Offline training means that the network has been pre-trained on a certain dataset on the CPU (by running the algorithm on a deep learning framework like Pytorch) and the learnt means and variances of the weights have been stored onto the hardware platform. The system is then used to make future predictions on input data.

Why is solving this problem important/ How is solving this problem beneficial?

With artificial intelligence becoming more and more ubiquitous, neural networks are being applied to almost every domain. This includes sensitive areas such as autonomous vehicles, healthcare, and security. In many real-time applications, there is no scope for incorrect decisions and not making a prediction is better than making the wrong one. A traditional neural network provides a prediction based on the input data but will do the same for data it isn’t trained for (image of a leopard in a cat vs. dog classifier) with high confidence. A BNN aims to solve this problem by not only providing the result but also providing how uncertain it is about the result. This is the case because the output is no longer a fixed point value, but a probability distribution. The variance of the output’s distribution can be used as the uncertainty measure to assess how confident the network is of its prediction.

What are the current state of the art techniques to solve this problem?

The fundamental hardware design requirements for a BNN are as follows:

A Gaussian random number generator (GRNG): In order to sample the weights from their respective Gaussian distributions, a Gaussian random generator would be essential to the design.

Multiplication between inputs and weights, followed by addition: This is the most fundamental operation for the forward propagation of information.

Activation function: The hardware implementation of the rectified linear (ReLU) / sigmoid/ tanh neuron.

[1] is a state of the art CMOS based (using only MOSFETS) BNN hardware acceleration scheme. It uses a linear feedback register to create a binomial distribution and then uses the binomial distribution approximation method to obtain a Gaussian random number. It has a memory unit that stores the learnt means and variances of the weights from offline training. A separate multiplication and addition unit and ReLU neuron unit is used for the forward propagation of input data.

In your project, what do you propose to improve the state of the art?

We propose a spintronic hardware based BNN to tackle the various shortcomings of the CMOS based design.

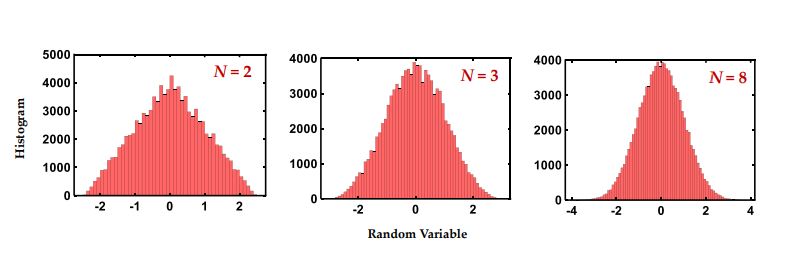

A two state MTJ can be thought of as a bit storage device, with the parallel state representing “1” and the antiparallel state representing “0”, by convention. One of the ways to switch the state of the MTJ is by passing a current through the device. The probability of state switching depends on the magnitude of the current passed. If the current value is set such that the MTJ would switch states with 50% probability, the passing of current through the devices can be visualized as the flipping of a coin that has an equal probability of heads or tails. Thus, if this is done with an array of ‘n’ MTJs, it would be equivalent to randomly selecting an ‘n’ bit number (a number between 0 and 2n -1) from a uniform distribution. By exploiting the central limit theorem, which states that the probability distribution of the average of N random variables sampled from any probability distribution tends to Gaussian when N is large, we can obtain Gaussian random numbers from the uniformly distributed ‘n’ bit numbers obtained from the MTJs.

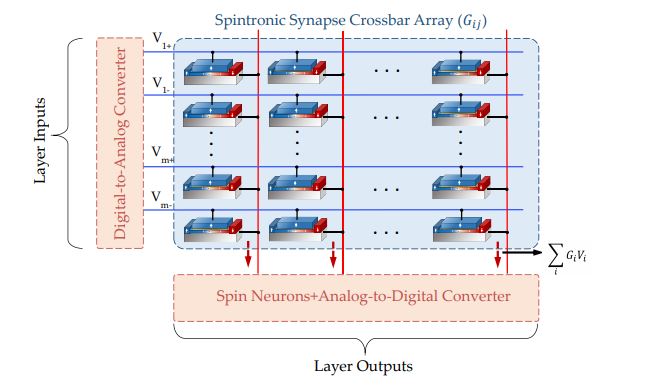

Figure 2: The spintronic crossbar array

The multiplication and addition operation is done using a spintronic crossbar array. Ohm's Law states that V/R = I or VmultG = I, where G is the conductance. Kirchoff’s Law states that if two or more currents are entering a node, the current exiting the node is the sum of these currents. Figure 2 shows the spintronic crossbar array. Each MTJ is used as a multi-state device, and the weight values are stored in these MTJs as their conductances. Each row has a voltage corresponding to the magnitude of the input data. Thus, the input is effectively multiplied by the weight and currents are summed along the column, which is equivalent to the summation operation during forward propagation.

The resultant currents act as inputs to spin based ReLU neurons [2], which produces an output voltage, which will be used as the input voltage for the next layer of the network.

Please describe your results.

A two hidden layer fully connected BNN with spintronic hardware was simulated, with each layer having 200 neurons. The network was trained on the MNIST dataset (digit recognition problem). The baseline accuracy (software implementation) of the network was found to 97.51% on the testing dataset, averaged over 10 forward propagations (weights are randomly sampled from their probability distributions in each forward propagation). The proposed hardware implementation has an accuracy of 96.98% on the testing dataset averaged over 10 forward propagations, due to certain device non-idealities and constraints. The total energy consumption of the scheme was evaluated to be 790.2nJ per classification, 24 times less than the CMOS based implementation in [1].

Figure 3: Probability distributions of random numbers generated using the spintronic GRNG by averaging N random variables.

The spin based hardware implementation also takes many orders of magnitude less area than the CMOS based implementation. The CMOS GRNG uses 1780 registers, whereas the spintronic GRNG uses just 24 MTJs and some peripherals, without compromising on random number quality (as shown in figure 3). In the CMOS based BNN, the weights of the network are stored in memory and have to be fetched every time they are needed for the multiplication and addition operations. This not only leads to additional area requirements but also extra power consumption for every time data is fetched from memory. The spintronic crossbar array solves this problem, which is known as the ‘Von Neumann bottleneck’, since the crossbar array is not only used for the storage of the weights but also the multiplication and addition operation described above. Hence, the utilization of ‘In-Memory’ computing helps save on area as well as drastically reduces power consumption.

What are some papers/resources that you would recommend others to read so that they can get to know more about this field?

To learn more technical details about this project, I would recommend reading this paper. To learn more about BNNs and how they are trained, I would recommend this paper. You can find the code for the implementation of a BNN here. This paper will be useful to learn more about spintronic devices and their various applications in Boolean and non-Boolean computing.

What future work can be done in this area?

Hardware acceleration schemes for BNNs are currently limited to offline trained systems. Spintronic hardware for online training of BNNs is an example of future work that can be done in this area and would be especially beneficial for real-time systems.

References

[1] Ruizhe Cai, Ao Ren, Ning Liu, Caiwen Ding, Luhao Wang, Xuehai Qian, Massoud Pedram, and Yanzhi Wang. 2018. “VIBNN: Hardware Acceleration of Bayesian Neural Networks”. SIGPLAN Not. 53, 2 (March 2018), 476–488.

[2] A. Sengupta, Y. Shim and K. Roy, "Proposal for an All-Spin Artificial Neural Network: Emulating Neural and Synaptic Functionalities Through Domain Wall Motion in Ferromagnets," in IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1152-1160, Dec. 2016.